The following are the different matrices for the secondary spread of African swine fever.

Oral-nasal excretions and secretions

The virus is present in both nasal and oral secretions of infected animals and can be detected even before its appearance in blood and clinical signs. The quantity of shed virus is relatively low, though sufficient to trigger new infections.

In the oral-nasal fluids, the virus is shed for a few days – two to four – while its half-life is not known. Oral and nasal fluids are likely to be involved in the direct contact spread of the infection.

Blood

The virus is detected in the blood of infected wild boars at two to five days – average is three days – post exposure. The detection of the virus in the blood is concomitant with the onset of clinical signs. The virus is massively shed in the blood where it can survive for 15 weeks at room temperature, months at 4C and indefinitely when frozen.

The blood contamination of soil, hunting premises and tools, including knives, clothes and cars used for transport of infected hunted animals are important sources for the local persistence and further spread of the virus.

Raw meat

The virus is present in the meat of sick animals too. Since the virus is resistant to putrefaction, it can survive for more than three months in meat and offal. It remains infective for almost one year in dry meat and fat, and it survives indefinitely in frozen meat. Also, the meat represents an important source for both the local maintenance and possible further spread of the virus. Frozen meat of infected wild boars can ensure survival of the virus for years and thus represents a possible source for new epidemics.

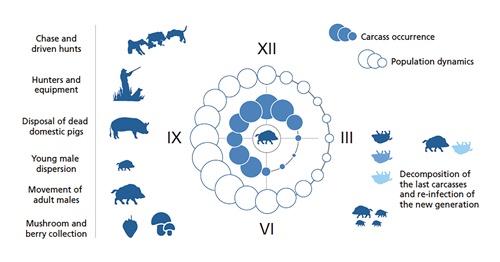

Figure 4: Endemic transmission cycle of African swine fever. The figure shows the endemic transmission cycle of ASF in a large continuous wild boar population and main natural mechamisms and factors facilitating sustained year-round circulation and progressive geographical spread. Note that Roman numerals denote months of the year.

Carcasses

As in meat, the virus can survive in whole carcasses for a very long time depending on ambient temperatures. A frozen carcass can maintain infectious virus for months, which means that the pathogen can overwinter even in the temporary absence of any live host and initiate a new transmission cycle when the defrosted carcasses are visited the following spring by susceptible wild boars.

In the natural history of ASF in the wild boar cycle, the virus survival in carcasses plays a crucial role. It outlives its host. Once an infected wild boar dies, the virus remains infectious in the carcass for an extended period of time.

In such an epidemiological framework, safe removal of carcasses from the environment and their disposal is one of the most important disease control measures, without which ASF eradication from wild boar populations is not possible.

Offal

The virus survival rates in offal are similar to those in carcasses. Whenever an infected animal is dressed in the field, the offal – including viscera, skin, head and other parts of the body – becomes an important potential source of the virus. Particularly in winter, when hunting activities take place, offal that has not been properly disposed of has the potential to increase the risk of secondary infections and the spread of the disease.

Faeces and urine

Both are infectious and the half-life of the virus is determined by the environmental temperature. ASFV survives longer in urine than in faeces. Its half-life in urine ranges from 15 days at 4C to 3 days at 21C. In faeces, virus half-life ranges from eight days at 4C to five days at 21C and the virus DNA is detectable from two to four years. The half-life of the virus is strongly affected by enzymes – proteases and lipases – produced by bacteria colonising faeces and urine.

Thus, the exact survival time in the forest where ASF is actively circulating is not fully comparable to the estimates obtained in laboratory conditions. However, in areas highly contaminated by infected faeces and urine, the risk of secondary spread of the virus will be more likely through such sources as contaminated boots, tyres or hunting tools. At feeding stations attended by many animals, contamination by infected faeces or urine could increase the rate of secondary infections.

At feeding stations attended by many animals, contamination by infected faeces or urine could increase the rate of secondary infections.

Soil

Viral DNA has been detected in the soil after the removal of the body of an infected wild boar. Even when the carcass has been removed, the soil where it rested can remain contaminated. More research is needed to understand the role of contaminated soil as a risk factor for disease transmission, addressing the survival of the virus – persistence of viable virus – in different matrices and ecological conditions.

Scavenging insects

It has been hypothesised that ASFV can potentially survive in insects – adult or larval stages – scavenging on infectious carcasses. However, despite the fact that maggots of the green bottle fly – lucilla sericata – and blue bottle fly – calliphora vicina – have been detected as contaminated with ASF DNA, the presence of viable ASFV could not be proven.

It is not known if the virus maintains its infectivity in other scavenging invertebrates. In any case, scavenging insects are attracted to wild boars, thus increasing the contact rates between infectious carcasses and susceptible wild boars.

Hematophagous insects and ticks

The stable fly – stomoxys calcitrans – is considered a mechanical vector of the virus capable of carrying the virus for 48 hours but their role in the transmission cycle in Europe has not yet been fully investigated. The role played by other blood-feeding arthropods is unclear, especially in the wild. Ornithodoros ticks, strongly involved in the natural ASF transmission cycle in Africa, do not occur in the currently affected parts of the European continent.

The virus is present in both nasal and oral secretions of infected animals and can be detected even before its appearance in blood and clinical signs.

Fomites

High environmental resistance of the virus implies that its transmission is possible via any fomite – including contaminated, non-living objects capable of carrying infectious organisms, such as shoes, clothes, vehicles, knives or equipment.

Food and kitchen waste

The high resistance of the virus means that thermally untreated food such as sausages, salami or ham, as well as food leftovers originating from infected animals – both domestic pigs and wild boars – and accidentally released into a wild boar habitat, can initiate an ASF epidemic. Food waste is considered the main source of the virus in the long distance spread of ASF.

Grass and other fresh vegetables

Infected wild boars could contaminate fresh vegetables – as in the case of green corn plants damaged by wild boars – adding grass or vegetables to the feed of domestic pig should be forbidden everywhere ASF is present in wild boar populations.