ABOVE: Environmental enrichment is often assumed to improve animal welfare, even in the absence of evidence for actual improvements.

Environmental enrichment is often assumed to improve animal welfare, even in the absence of evidence for actual improvements.

In addition, the various definitions of EE raise varying degrees of expectations regarding improvement to animal welfare.

The review paper, ‘An effective environmental enrichment framework for the continual improvement of production animal welfare’ – published online by Cambridge University Press – proposes a new framework to categorise EE based on animal welfare outcomes, economics and practicality.

The authors considered the literature on EE for farm animals – laying hens, meat chickens, sows, cattle and sheep.

They also surveyed stakeholders (n = 26) – industry representatives, researchers, welfare officers and veterinarians – to evaluate the feasibility of different forms of EE.

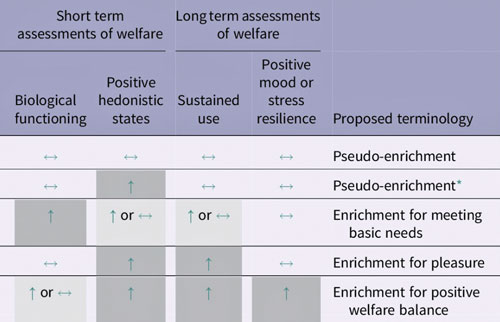

Using the new framework, four categories of EE are identified:

- Pseudo-enrichment – which is ineffective because animals do not want it and it does not improve physical health or biological functioning

- EE that meets basic needs – that is improves health and biological functioning

- EE for pleasure – things that animals want but do not necessarily improve health, biological functioning or economic gain

- EE for positive welfare balance – positive experiences outweigh negative experiences.

The proposed framework requires robust animal welfare assessments based on a suite of short and long-term indicators.

According to their analysis of the literature, 67 types of EE can improve farm animal welfare.

However, only about a third of these types of EE are currently used by industry, suggesting failure to translate research into practice.

The authors recommend that effective EE should improve animal welfare and be practical and economically viable.

In addition to the RSPCA’s inclusion in the quarterly Science Update above, the article extracts below give a more comprehensive insight into the study – the full version of which can be viewed at

Baseline environments are likely to affect the impact of enrichment provision on animal welfare.

Animals housed in barren environments are likely to show disrupted biological functioning and a pessimistic mood and therefore, some items may evoke greater improvements to welfare compared to the same enrichment item in a more complex environment.

As an example, deprivation of essential stimuli leads to sensitivity to rewards, as such the experience and value of an environmental enrichment will change as standard or baseline environments do.

This was a critical component that our framework considered, such that we focused on the magnitude of the improvements to animal welfare after the provision of environmental enrichment item or programme that can describe the improvements, even as minimum housing of production animals change.

Table 1. Proposed re-classification of environmental enrichment provided to animals based on both short and long-term assessments of welfare indicators.

As such, this framework focused on continual improvements to animal welfare after the provision of enrichment, which negates a ‘one enrichment fits all’ solution – as an example, ‘chains’ are enriching to pigs.

As continual improvements are made to the standard environments of intensively housed animals, this framework offers flexibility to assess the effectiveness of enrichments when they are added to the ‘standard’ or ‘typical’ housing environment.

This framework does not dictate the standard intensive environment animals ought to be housed in, this has and will likely continue to change as social norms evolve.

Rather, we provide a framework to indicate the relative animal welfare improvements after the provision of enrichment that can be used as evidence provided to consumers, regulatory bodies and producers.

Therefore, this framework should be used to indicate the relative improvement from the ‘industry standard’ relative to time, place and market.

The framework presented in this study provides a guide for considering the effectiveness of environmental enrichment to improve animal welfare at the group level and does not account for individual differences between animals.

Use and therefore effectiveness of enrichments may be related to individual differences caused by variation in previous experience, temperament or genetics, which will result in heterogenous improvements to animal welfare within the group, but an overall improvement for the flock, herd or drove.

Our survey data indicated that, of the enrichments identified in the literature search to improve animal welfare (n = 67 enrichment items, programmes, supplementary material), only 33 percent on average were currently utilised by industry – 6 percent pork industry, 34 percent egg industry, 56 percent chicken meat industry.

These data may suggest a disconnect between research and industry – a poor response rate makes our results inconclusive but similar findings have been reported elsewhere.

This may be related to concerns with practicality – actual or perceived – or economics.

Indeed, the survey showed that costs were industry’s greatest perceived barrier to implementing enrichments, which has also been recently reported.

As highlighted by our survey, the assessment of economic benefits and costs for effective and practical enrichments is affected by familiarity with the enrichments, as well as their implementation and maintenance costs – such as material.

Broader benefits from providing animal enrichments – access to retailers, gaining or maintaining social licence – may not generate an immediate economic return but may contribute to a competitive advantage of a livestock production business, which can be difficult to value in an economic benefits and costs assessment.

Further, the time lag between input and benefit may make it difficult for producers to recognise the positive impact of enrichment provision on the productivity and sustainability of their enterprise.

This framework provides a structure to discuss the links between animal welfare outcomes and productivity improvements and premium price returns.

Animal welfare implications

This body of work provides a framework for livestock producers to ensure that the provision of enrichments is effective, in the sense that they are feasible and economical to implement and lead to actual improvements to animal welfare.

As such, this framework focuses on the outcome of enrichment provision rather than the intent.

Changing the narrative from simply ‘ticking a box’ when providing enrichments also provides the flexibility required for continual improvements to animal welfare, even when baseline or industry standard environments evolve.

Conclusion

This paper proposes a framework to re-define and classify effective environmental enrichments.

It incorporates four welfare outcome categories – which are science-based and may be utilised in a variety of contexts including – to inform on the development of animal welfare legislation, assurance programmes, product differentiation and labelling.

The impact of the enrichment is the focus rather than the intent and our approach aims to ensure a continued improvement to production animal welfare.

We highlight knowledge gaps in the scientific literature regarding livestock enrichment programmes, that would benefit from both short and long-term assessments to measure suffering, pleasure and welfare balance.

The inclusion of practicality and economics promotes interactions between researchers, regulatory bodies and industry to develop proposed enrichments which are industry relevant and feasible to implement.

This framework can help stakeholders communicate the effects of their enrichment programmes on animal welfare to the public and consumers and create genuine improvements to animal welfare.