ABOVE: Early life contact with humans can play a substantial role in shaping piglets’ behavioural and physiological responses to stress.

An experiment undertaken by collaborative researchers from the University of Melbourne, Rivalea and the University of Queensland – entitled ‘Positive human contact and housing systems impact the responses of piglets to various stressors’ – provided evidence that regular positive human interaction reduces pigs’ fear of humans and husbandry procedures imposed by stockpeople.

Authored by Megan E Lucas, Lauren M Hemsworth, Rebecca S Morrison, Alan J Tilbrook and Paul H Hemsworth, the following are excerpts from the research, which can be found in its entirety via mdpi.com

Simple summary

Early life experiences such as contact with humans, maternal care and the physical environment can play a substantial role in shaping behavioural and physiological responses to stress.

This experiment studied the effects of lactation housing systems and human interaction on stress in young pigs.

We hypothesised that piglets handled in a positive manner and reared in loose farrowing and lactation pens – with increased opportunity for interaction with their dam, greater space and more complexity in their physical environment – have improved stress resilience than piglets reared in traditional farrowing crates with routine contact from stockpeople.

In both housing systems, providing regular opportunities for positive human interaction reduced piglets’ fear of humans and routine husbandry procedures imposed by humans, and reduced the number of injuries obtained after weaning.

However, contrary to the expected findings, piglets from loose farrowing and lactation pens were more reactive to capture by a stockperson, more fearful of novel and human stimuli, had more injuries during the lactation period and were more likely to perform behaviours which may be indicative of reduced coping after weaning.

Whether these effects are specific to the loose farrowing and lactation system studied in this experiment or are reflective of other loose systems requires further research.

Introduction

Commercial pigs are exposed to several stressful situations as part of routine production, including painful husbandry procedures, close contact with stockpeople, exposure to novel environments, weaning and mixing with unfamiliar pigs.

Stress resilience, which refers to the ability of an individual to cope with and recover from stress, has obvious implications for the pig industry, as an impaired ability of pigs to cope with these routine stressors is likely to negatively affect pig welfare and productivity based on studies in non-human primates and rodents.

Stress resilience can be shaped by several early-life environmental inputs, and for pigs, the physical environment, maternal care from the sow and interactions with humans are likely candidates.

Farrowing crates remain the most widely used system for rearing pigs during the lactation phase, though increasing concern for animal welfare has led to the design of several alternative farrowing and lactation housing systems, which allow free movement of the sow.

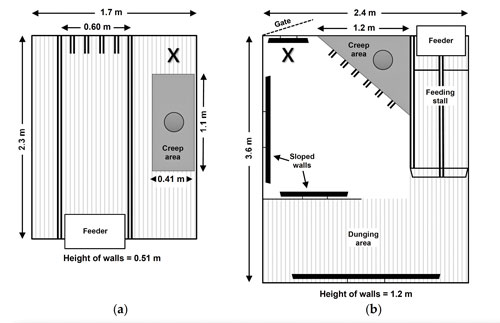

One example is the PigSAFE pen.

The piglet and sow alternative farrowing environment is a loose farrowing and lactation system that was designed to optimise sow welfare and piglet survival, while maintaining ease of management and commercial viability.

PigSAFE pens offer greater space and contain features such as sloped walls, varied flooring and separate sections for feeding, nursing and elimination, and as such are considered to be a more complex environment than the traditional farrowing crate.

Figure 1. Layout and dimensions of the two housing systems: (a) farrowing crate (FC); (b) loose pen (LP). X denotes the position of the experimenter during the imposition of the positive human contact treatment.

In addition, PigSAFE pens offer greater opportunity for sow-piglet interaction, which may have implications for the level of maternal care piglets receive.

Sows in other loose lactation systems show improved maternal behaviour, as evident by increased responsiveness to piglet vocalisations and more frequent interactions with their piglets in comparison to sows from farrowing crates.

In loose housing systems such as PigSAFE, the increased environmental complexity and the greater opportunity for maternal care may contribute to improved stress resilience in piglets.

While research on the PigSAFE system is sparse, there is evidence that pigs reared under different maternal and/or physical conditions vary in their responses to stressors routinely encountered in production.

Pigs from farrowing crates showed greater cortisol responses after ear tagging and restraint compared to pigs from outdoor pens, and greater cortisol responses after transport compared to pigs from larger crates and pens enriched with straw.

The ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte cells after husbandry procedures was higher in pigs from barren environments than pigs from environments enriched with newspaper, soil, balls and rope.

Play behaviour was performed more frequently and occurred earlier in life in piglets in loose pens, which suggests the farrowing crate environment negatively impacts the development of normal social skills.

This can affect how pigs respond to social stressors, since after mixing with unfamiliar pigs at weaning, belly nosing and manipulative behaviours were performed more frequently by pigs from farrowing crates than loose pens.

Furthermore, pigs reared in loose pens spent more time exploring food after weaning and tended to show improved growth compared to piglets from farrowing crates.

Acute phase proteins such as haptoglobin have also been used to study stress in pigs and may provide information on the magnitude of the stress response to weaning.

Many challenges faced by commercial pigs involve close contact or handling by stockpeople, and thus responses to these challenges are affected by the level of fear pigs have towards humans.

Piglets that had experience with a handler who moved unpredictably and shouted during routine feeding and inspections demonstrated less resting, and more escape attempts and agonistic interactions after weaning, in comparison to piglets that had experience with a handler who moved carefully and used a soft tone of voice.

Talking softly and imposing gentle tactile contact such as stroking and scratching upon approach is perceived positively by pigs and reduces fear of humans.

Patting and stroking during suckling bouts reduced the duration of escape behaviour in piglets during husbandry procedures conducted at two days of age and capture at 15 days of age, and daily patting and scratching reduced the avoidance responses of sows to stockpeople imposing pregnancy testing and vaccination.

Pigs can remember positive interactions with humans for at least five weeks, and when these interactions take place early in life the effects may be sustained for up to 18 weeks.

The effects of providing pigs with opportunities for positive human interaction extend beyond reducing fear of humans.

Piglets that were stroked while being held showed reduced fear of tactile contact by familiar and unfamiliar people, but also performed more play behaviour and vocalised less in a novel arena, suggesting that the handling treatment reduced both fear of humans and novel situations.

Positive handling has also been reported to reduce tail biting behaviour in weaner pigs, though the handling treatment in this experiment involved attracting piglets with chopped straw, which is a potentially confounding factor.

Weight gain was higher in piglets habituated to human handling and human presence.

The presence of a familiar human after social isolation reduced the duration and frequency of piglets’ vocalisations, which suggests that familiar people may even buffer stress when pigs are exposed to challenging situations.

Since maternal care, the physical environment and interactions with humans can impact stress resilience, the aim of this experiment was to study the effects of farrowing and lactation housing systems and positive human contact on piglets’ responses to routine stressors.

The hypothesis for this experiment was that piglets reared in loose farrowing and lactation pens with opportunities for positive human interaction show improved stress resilience, compared to piglets reared in traditional farrowing crates with routine contact from stockpeople.

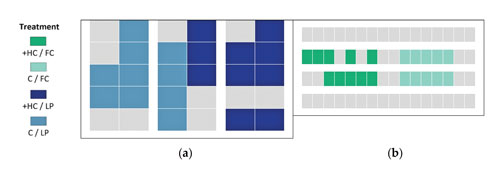

Figure 2. Allocation of positive human contact (+HC) and routine human contact (C) litters: (a) loose pen (LP) room; (b) farrowing crate (FC) room. Grey boxes in both housing systems represent non-experimental litters.

Conclusions

While sow and piglet welfare are generally considered to be superior in loose farrowing and lactation systems, the results from this experiment showed that piglets reared in loose pens displayed a higher intensity of escape behaviour when being captured during processing and were slower to approach and physically interact with a novel object and an unfamiliar human compared to piglets from farrowing crates.

Furthermore, piglets reared in loose pens had more injuries during lactation and were more likely to be upright, vocalising, nosing a pen mate and nosing the floor after weaning.

While there were no effects of housing system on stress physiology 45 minutes after processing or 1.5 hours after weaning, these results raise questions that require further research on the ability of piglets reared in loose pens to cope with stressors such as exposure to humans, novelty, husbandry procedures and weaning.

Whether these effects are specific to the PigSAFE system studied here or are reflective of other loose systems is unknown.

The PigSAFE system offers greater space and structural complexity and increased opportunities for interaction with the sow, however, in this experiment the PigSAFE environment was more restrictive in terms of piglets’ contact with humans and non-littermates.

For piglets in farrowing crates, the increased visual, auditory and olfactory contact with stockpeople and other pigs may be adaptive and contribute to improved stress resilience by allowing piglets more opportunities to overcome mild stress.

This experiment also provides evidence that regular positive human interaction reduces pigs’ fear of humans and husbandry procedures imposed by stockpeople.

However, more research is clearly necessary to understand the effects of positive human contact on the injuries and stress physiology of pigs after weaning.

The effects on stress physiology in particular highlight the need for a multifaceted approach to the welfare assessment of pigs.

Additionally, whether the effects of the positive human contact treatment and those of the early housing system are sustained long-term requires further investigation.

For more information, email Megan on megan.lucas@unimelb.edu.au or Paul on phh@unimelb.edu.au

Megan Lucas and Paul Hemsworth

University of Melbourne Animal Welfare Science Centre