ABOVE: Several forms of animal killing are a necessary component of our inescapable involvement in a single functioning finite global food web.

An unavoidable component of human existence.

Killing animals has been a ubiquitous human behaviour throughout history, yet it is becoming increasingly controversial and criticised in some parts of contemporary human society.

Over a three part series, researchers from around the globe review 10 primary reasons why humans kill animals, discuss the necessity or not of these forms of killing and describe the global ecological context for human killing of animals.

The article can be viewed in its entirety at sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969723039062

Humans historically and currently kill animals either directly or indirectly for the following reasons:

- Wild harvest or food acquisition

- Human health and safety

- Agriculture and aquaculture

- Urbanisation and industrialisation

- Invasive, overabundant or nuisance wildlife control

- Threatened species conservation

- Recreation, sport or entertainment

- Mercy or compassion

- Cultural and religious practice

- Research, education and testing.

While the necessity of some forms of animal killing is debatable and further depends on individual values, the authors emphasise that several of these forms of animal killing are a necessary component of our inescapable involvement in a single functioning finite global food web.

They conclude that humans and all other animals cannot live in a way that does not require animal killing either directly or indirectly, however humans can modify some of these killing behaviours in ways that improve the welfare of animals while they are alive or to reduce animal suffering whenever they must be killed.

Encouraged is a constructive dialogue that accepts and permits human participation in one enormous global food web dependent on animal killing and focuses on animal welfare and environmental sustainability.

Doing so will improve the lives of both wild and domestic animals to a greater extent than efforts to avoid, prohibit or vilify human animal-killing behaviour.

Widespread criticism of killing animals occurs at all scales, including anglers, recreational hunters and wildlife scientists.

Introduction

The killing of animals by humans has been a common practice throughout history and this pattern continues in the present age.

Countless animals are killed daily, either for direct consumption or indirectly through competition for resources, and the nutrients released through this process ultimately find their way back into the environment.

Ecology textbooks refer to this as the ‘food chain’ or ‘food web’.

Animal killing by humans and animals is ecologically ubiquitous, yet some sectors of contemporary human society condemn, criticise or oppose animal killing by humans, attempting to prevent or minimise human involvement in the global food web.

Some more extreme adherents have even suggested that non-human predators might also be prevented from killing their prey.

Criticism of animal killing comes in many forms.

Modern hunter-gatherers and subsistence farmers are criticised for killing wild animals to feed themselves or to protect what little crops they can produce.

Livestock producers are criticised for raising and then killing domestic livestock and the wild predators and competitors of their livestock.

Crop producers face the same criticism when they kill animals during tilling, during harvest or when they protect their crops from being eaten by other animals.

Conservationists are criticised for killing exotic, invasive or overabundant animals to protect native biodiversity.

Hunters are criticised for killing animals for food, sport or pleasure.

Cultures and religions are criticised for killing animals and disregarding animal suffering during various rituals.

Researchers, scientists and educators are also criticised for performing dissections or experimenting on and killing animals in laboratories or for field-testing ecological hypotheses related to animal killing.

This widespread criticism of killing animals occurs at all scales.

It is directed towards global food industries such as the beef, dairy, pork, poultry and egg industries.

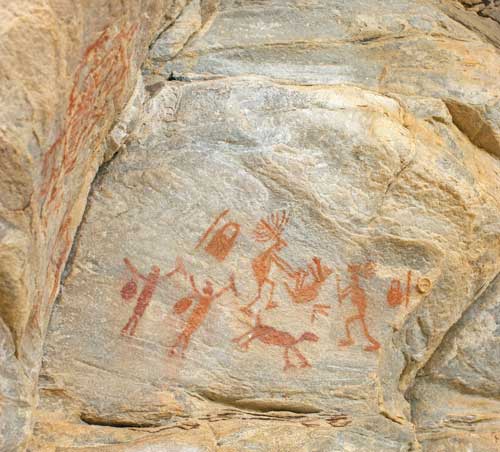

The killing of animals by humans has been a common practice throughout history and this pattern continues in the present age. Indigenous people cave paintings from the Xique Xique Archeological site at Carnaúba dos Dantas, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil. Photo: Vitor Paladini

As well as government agencies at all levels, including for example the US Department of Agriculture or Australian state and local governments.

And is even targeted towards specific individuals including anglers, recreational hunters, wildlife scientists and meat eaters.

Support for this criticism arises from a variety of perspectives.

As examples, some have argued that animal killing by humans is immoral, unethical, irreligious, unjust, unacceptable or just plain wrong.

Others claim that animal killing ignores ‘animal personhood’ and that animals should have rights equal to humans – that animal abuse, violence or murder is unacceptable and criminal – and many people have held and still hold this belief.

Many also view the act of animal killing as cruel or harmful, regardless of how it is accomplished or how instantaneous or painless it might actually be, and hence advocate for only non-lethal practices or complete cessation of animal killing, ostensibly to stop animal suffering.

Some have argued that animal killing does not resolve some of the issues it aims to address and is therefore unnecessary – for example, it does not stop depredation of livestock or does not contribute to the conservation of endangered species.

Others have further argued that killing animals is an inefficient way to obtain nutrition and that animal killing will be reduced by seeking our life-sustaining nutrients from lower trophic levels – that is, vegetarianism or veganism.

The authors agree with many of these perspectives and do not attempt to address or dispute each of these claims or worldviews.

Rather, as valid, strongly held and important as these differing views might be, they consider them largely tangential to an ecological perspective on animal killing by humans and our undeniable role at the apex of the global food web.

The philosophical, medical, veterinary, husbandry and ecological literature is replete with robust debate on the acceptability of killing various animals in diverse circumstances, and it is clear that many people support or accept animal killing in one way or another while some others oppose it.

However, much of the ‘for versus against’ multidisciplinary literature on this subject typically fails to put contemporary animal killing behaviour by humans into an evolutionary or ecological context, and an explanation for why humans kill animals and why we cannot avoid it has not been well articulated.

Humans do not live independently of other species.

We are an inescapable part of the global food web and our action, inaction and mere presence on Earth has diverse consequences for animal life.

The disciplines of anthropology, archaeology, climate change, ecology, evolutionary biology, religious studies, philosophy and ethics, taxonomy and others implicitly attest to the interconnectedness of humans with other living organisms.

We consider this a self-evident fact that should be understood by, or at least understandable for, most people.

Over three parts, the authors will provide a brief overview of 10 primary reasons or categories of reasons why humans kill animals, or 10 primary forms of human animal-killing behaviour.

Associate Professor Benjamin Allen, research co-author and wildlife management and research team leader at the Institute for Life Sciences and the Environment at the University of Southern Queensland.

The broad definition of killing includes the intentional and unintentional actions and inactions of humans that directly or indirectly cause animal death, because any alternative or more restricted definition would knowingly omit important modes of human animal-killing behaviour.

Animal killing is also multifunctional.

Thus the 10 reasons described are non-exclusive and overlap in many cases, some may also be considered to fall into multiple categories, and the stated categories might also be reorganised in an alternative variety of acceptable ways.

Though the rationale might apply to many types of animals, the discussion focuses on vertebrate animals, which are almost universally recognised as being sentient.

The authors argue that killing such animals is an unavoidable component of human life on Earth that might be reduced in some cases but is impossible to eliminate.

They further argue that ethical debate over whether or not to kill animals is unhelpful, and that a critical analysis of when and how to kill animals is much more relevant and consequential to improving animal lives.

Encouraged is a future focus on animal welfare and the ecological sustainability of our animal-killing behaviours, rather than focussing on binary ethical or philosophical issues such as ‘killing or not killing’ or ‘lethal or non-lethal’ animal management.

Though human dimensions – including worldviews, values, perceptions, attitudes, motivations, emotions and behaviours – are important drivers of why humans kill or do not kill animals, the primary aim was not to systematically review the sociological or psychological literature on anthopogenic reasonings for killing animals.

Rather, the aim is to ecologically contextualise animal killing behaviour by humans, describe some of the implications of this for contemporary debates about animal ethics, and so provide a resource for those engaging in discussions about the permissibility and acceptability of killing animals.

The authors’ intended outcome is to redirect some of the philosophical and ethical debates away from intractable tensions between fundamentally different and somewhat theoretical worldviews towards applied issues that have a greater capacity to collectively improve the lives of both animals and people.

Next month, Part 2 will cover the first five of the 10 reasons of why humans kill animals and why we cannot avoid it.

Ben Allen

University of Southern Queensland