ABOVE: Pork producer Mark McLean has improved sow productivity on both Riverhaven Enterprises’ operation farms through improved farm management, genetics and staff training and development.

Stockmanship is an occupation that requires expertise, endurance and empathy.

Stockpeople have a direct impact on agricultural animal welfare and productivity.

Unfortunately, stockpeople are undervalued and their role in agricultural sustainability overlooked.

A shortage exists for good stockpeople, and investigations are needed that examine the impact of higher stockperson salaries and education on employee behaviour, employee retention, applicant pools, animal welfare and sustainability.

Integration of husbandry education into university curricula, conducting personality assessments on potential employees and promoting occupational awareness may facilitate the development of a long-term highly skilled stockperson workforce.

Stockpeople are the stewards of our food animals and play a critical role in agricultural sustainability.

Yet, there is a disconnect between the value that is placed upon their role in animal agriculture, their compensation and the scope of impact they can have on the animal’s productivity, public perception of animal agriculture and animal welfare – in the US and abroad.

The daily care, long-term health and productivity of our food animals are the responsibility of the stockperson.

Stockpeople are usually regarded as itinerant and unskilled, which can result in managers making minimal investments into their development as employees, and producers are increasingly reporting difficulties in identifying qualified applicants.

However, because of the critical role the stockperson plays in animal production and welfare, the human resources devoted to selecting, training and managing these employees need to reflect modern employee management, as found in other industries.

Stockmanship is a representation of animal welfare itself, where the entirety of the animal, its physiological, behavioural and emotional state is managed by their human caretaker, and thus requires a complex and deep skill set to properly implement.

As described by Hemsworth and Coleman, the stockperson is required to have:

…a basic knowledge of both the behaviour of the animal and its nutritional, climatic, housing, health, social and sexual requirements together with a range of well-developed husbandry and management skills to effectively care and manage farm animals.

For instance, farm personnel may have knowledge and skills in a number of diverse management and husbandry tasks such as estrus detection and mating assistance; semen collection, semen preparation and artificial insemination; pregnancy diagnosis with ultra-sonography; artificial rearing of early weaned animals; milk harvesting; controlling and monitoring of feed intake to optimise growth, body composition, milk production and reproductive performance; pasture management to optimise pasture production; routine health checks; monitoring and adjusting climatic conditions in indoor units; administering antibiotics and vaccines; shearing and crutching of sheep, teeth and tail clipping of pigs; castration of males; and effective and safe animal handling.

These are skilled tasks and farm personnel are required to be competent in many of these tasks.

Substantial resources have been invested to enhance the genetic merit of livestock, maximise their reproductive capacity and optimise the quality of the nutrition they receive.

Husbandry guidelines and policies have been developed and legislation passed with the intent of promoting good animal welfare, however the primary emphases of these initiatives are on housing requirements and pain management.

The regulation of animal care has focused primarily on how animals are housed and by what means they are managed.

What is sometimes forgotten is that the individual often responsible for implementing such changes is the stockperson.

Therefore, the impacts from these efforts may have substantial positive, or negative, consequences depending upon the stockperson’s actions.

Investing in high-quality, well-trained and appropriately compensated stockpeople must become a national priority within the food industry.

However, a disconnect exists between stockperson pay, the level of knowledge and skill required to perform the job, and the impact these employees can have on the overall productivity and welfare of the animal.

The duration of time stockpeople spend interacting with animals is substantially longer and requires more knowledge and skill than the interactions they have with the truck driver that delivers the animals to the slaughterhouse, yet the truck driver is paid almost twice as much as the stockperson.

In concert with the change in society’s expectations regarding animal welfare, these societal expectations must expand to acknowledge stockpeople as professionals, and they must be treated as such.

A need for more animal scientists exists across all disciplines, including stockmanship – which requires skill, knowledge and training similar to other animal science disciplines.

Awarding stockpeople the knowledge and respect they deserve, and incorporating stockmanship skill development and training into the undergraduate curriculum, will aid in creating a long-term satisfied skilled workforce.

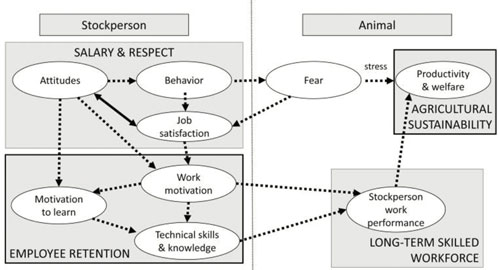

Investing in stockpeople can improve workforce morale and have positive impacts on productivity, animal welfare on farm, and has the potential to influence the overall sustainability of animal agriculture – see Figure 1.

Figure 1: The human-animal interaction in relation to stockperson salary, job retention and sustainability.

Employee retention is a challenge for many producers across all animal product sectors.

Despite the issues associated with maintaining long-term employees and their subsequent low financial compensation, animal industry employees enjoy their work.

Historical survey data demonstrated that 74 percent of farm workers were satisfied with their work and job satisfaction, and this enjoyment was increased with the implementation of new technologies.

A majority of Australian swine and dairy stockpeople expressed a strong enjoyment for working with animals on a daily basis.

This is an ominous trend that may have unforeseen consequences – loss of husbandry knowledge, not enough stockpeople to care for livestock – to the future of our food supply.

One strategy that may attract more people to the occupation may be providing salaries and benefits that are competitive with salaries that offer the same standard of living as an urban occupation requiring the same level of knowledge and skill.

Another strategy is to increase awareness of employment opportunities and to empower those from urban backgrounds with little inherent knowledge and experience to engage with agricultural animals and to utilise their skill set in new and unique ways.

The enjoyment of working with animals combined with the positive impact that technological advancements have on worker satisfaction present a promising opportunity for future stockpeople in animal agriculture.

The onset of precision agriculture and the implementation of new technologies within the animal agricultural industry will provide ample opportunities for stockpeople to engage in animals while utilising cutting-edge technologies.

Therefore, there is a need to identify individuals that are highly motivated to work with animals and are also technologically savvy.

Fortunately, many of the individuals that may become stockpeople will most likely be from urban and highly technological backgrounds.

Because precision agriculture is the future of food animal production, this suggests that those who choose to enter into this line of work will find themselves highly satisfied with what they do for as long as they choose to do so.

To read the article in full, visit academic.oup.com/af/article/8/3/53/5043179

Courtney Daigle and Emily Ridge

Department of Animal Science

Texas A&M University